-

Finch Frolic is for Sale

Four varieties of banana in the tropical area. The almost two acres of permaculture food forest and the split-level home of Diane and Miranda will be listed for sale April 5th, 2024. Over 40 varieties of food-bearing fruit and nut trees and plants, plus herbs, vegetables, native plants, timber bamboo and ornamentals. Over 112 species of bird have been recorded on site by Miranda as well as over 40 species of butterfly and the same of moth. Slender salamanders, frogs, coyotes, opossum, racoon, bobcat, skunk, and many more native animals find respite in this chemical-free garden. The three bedroom home built in the 80’s is move-in ready, and can have a kitchen and bathroom updating when ready. The Pergo-type floor resists scratches, newly painted inside and out, new roof 2020, double-paned windows, two fireplaces, new waterheater 2023. Tiled entryway by mosaic artist Jane Engleton; Stars and Moon small bedroom painted by local artist Melissa Ledri. Refrigerator, washer and dryer, split AC/heat installed last year (no more propane tank!), enough solar to run the house and well pump and still receive a check from SDGE. A 700 gallon and four 50 gallon water tanks capture roof water. All irrigation comes from a well, and the pump is run from solar. A small greenhouse, two sheds, composting toilets, an outdoor sink, and a freezer-turned-worm bin along with eleven vegetable beds filled with mature beautiful soil. This garden has educated thousands of people over the last decade on methods of chemical-free gardening and conserving nature. We would love for permaculturalists to continue to love it and the animals that call it home. $850,000. Please do not leave questions here, contact: Greg Farrell

Real Estate Agent Lic# 01203492 (949) 588-8134

gregfarrell@firstteam.com

gregfarrell.firstteam.com

A wonderful screened-in porch.

Small fenced yard for pets and get-togethers. Chain link is around most of property.

Windowseat overlooking small lined pond and bird watching area.

Composting toilets and large shed.

Dwarf peach is one of over 30 species of fruit trees and shrubs

Many natives such as Western Redbud

Smaller bedroom painted Stars and Moons by local artist Melissa Gregg Ledri

Chemical-free habitat.

Rain catchment basins to sink all rainwater.

Inquisitive visitors to the large unlined pond.

Timber bamboo that is also edible, and non-invasive.

One of two fireplaces, this one with insert.

A 700 gallon tank captures roof water, and has submersible pump.

Outdoor sink (logs help lizards to climb free)

Wisteria!

Welcome to the garden.

-

Aphid Predators II

A WALK ON THE TINY SIDE

Remember this image of a sneaky syrphid fly larvae? Well, what I didn’t point out before was that there’s an even sneakier attendee at this aphid-nomming party. And she’s that little black line across the white leaf vein in the top middle of the photo: a parasitoid wasp.

Parasitoid wasps are pretty full-on — their simple life functions can include grotesqueries you thought only originated in the imaginations of sci-fi script writers. But they’re part of the complex web of ecological checks and balances in their systems.

The difference between parasitic and parasitoid is that a parasitic animal generally doesn’t kill or even directly seriously harm the host; it needs the host to continue functioning so that it can support the parasite. A parasitoid uses the host up in the process of supporting its own growth and/or reproduction.

That sneaky parasitoid lady and her cohort are the authors of the scene of destruction above. What look like little brown bumps on my Brussels sprouts leaf are in fact the corpses of aphids: the dried, hardened exoskeletons of used-up hosts. You can even see a small, round hole in the top of one — the door the exiting parasitoid punched out and left open behind it.

Parasitoid wasps like this one home in on the distinct chemicals released by the feeding and typical drama (like terror over a syrphid fly larva attack) of an aphid colony. Fertilized females settle on leaves and begin their prowl.

They’re looking for nice, juicy aphids that will be able to feed their grubs to adulthood. With a quick stab of her ovipositor, a female wasp injects a single egg into a chosen aphid, then prowls on. Once that tiny egg hatches, however, the aphid will slowly be hollowed out from the inside by the hungry, growing grub, until only a husk is left and the mature wasp breaks its way out, exercising its brand-new wings in flight for the first time.

The world is made up of opportunities being taken: everything is a resource and every resource is a chance for an existence to bloom. Sometimes, that existence is just really horrific. But it works for them and it works to create a functioning ecosystem — dynamic equilibrium — so we can all actually be very grateful for the parasitoid wasps.

Creeped out, but grateful. -

Aphid Predators

A WALK ON THE TINY SIDE

Another blooming colony of cabbage aphids (Brevicoryne brassicae) on my brave Brussels sprouts: a familiar sight, especially as the weather warms.

But wait — what’s that?

That! The green thing!

It may look a lot like a cabbage white butterfly (Pieris rapae) caterpillar, but it’s definitely not. Take a closer look and you’ll see that rather than a mouthful of sprout leaf, this little green guy is munching on aphid.

One of the most numerous, in terms of species, groups of animals on Earth are the flies, order Diptera. Like any large family, there are some gems, some bad apples, some neutrals — and of course, all that depends on your point of view. To aphids, larvae of some Syrphid flies (family Syrphidae) are stone cold bad-‘uns.

Also known as ‘flower flies’ and ‘hover flies’, these natty little fellows pull a lot of weight (each species in its own way) in both natural and altered ecosystems. Their secret is in their adaptable nature: they’re able to take to human-made environments, so are often some of the only native wildlife in housing developments.

The tellingly-named four–spotted aphid fly, Dioprosopa clavata. Most species in North America as adults mimic bees with yellow, black and striped uniforms and certainly rival and even surpass native bees in pollination services (bees are generally more sensitive in many ways and so are more often excluded or eliminated from habitats). They eat nectar and pollen, as bees do, thus the common name ‘flower fly’.

Flies’ eyes are very distinctive and always give away dipterid mimics passing as other insects — you can’t hide those flyin’ eyes, Copestylum avidum! And of course, most syrphid fly larvae are voracious predators of aphids, making them powerful elements of any garden’s pest management system (a.k.a. ecosystem). Be sure to make friends with yours! Get in touch with Pest Control Cincinnati

- Breads, Gardening adventures, Health, Heirloom Plants, Hugelkultur, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Planting, Recycling and Repurposing, Seeds, Soil, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian

Growing Cornmeal

Sweet corn is a wonderful summer treat; although you can freeze it, is never as good as picked, steamed and eaten within hours. However hard corn can be dried, ground and stored for use throughout the year. Some varieties that aren’t super sweet can be eaten fresh or left to go hard for grinding. Miranda and I have fallen in love with growing and grinding colored corn. They are not just for Thanksgiving decorations anymore!

We’ve grown Indian corn and small cute popcorn. We’ve also grown the lovely Glass Gem Corn, with its opalescent pastel colors that was all the rage for the last few years. It made a lovely lightly colored cornmeal.

Last year we planted Oaxacan Green dent and black corn. Wow. The black corn was the most successful, growing about 12 feet tall.

The black variety was Maiz Morado or Kulli Corn, from Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds. It had many aerial roots, which were black- actually a very deep purple- growing from several nodes.

The black corn began to peek out from the husks and it was magnificent.

We harvested the ears and let them lie on our warm porch out of the sun to finish drying. The stalks we tied up for Halloween and Thanksgiving decorations, and then they went into filling a raised bed.

When it came time to shuck the ears, we marveled at the color of the kernels. They were spectacular; so were the green dent.

Even better, the inside of the husks were colored, too. We dried them and saved them for tamales.

For New Year’s Eve, we stripped the dried kernels from the cobs; not a difficult process and one we could do in the evening after dinner while watching old Time Team reruns on YouTube.

When ground, the black corn meal was a light purple. We use our VitaMix’s special grain grinding container, but a normal one would work as well.

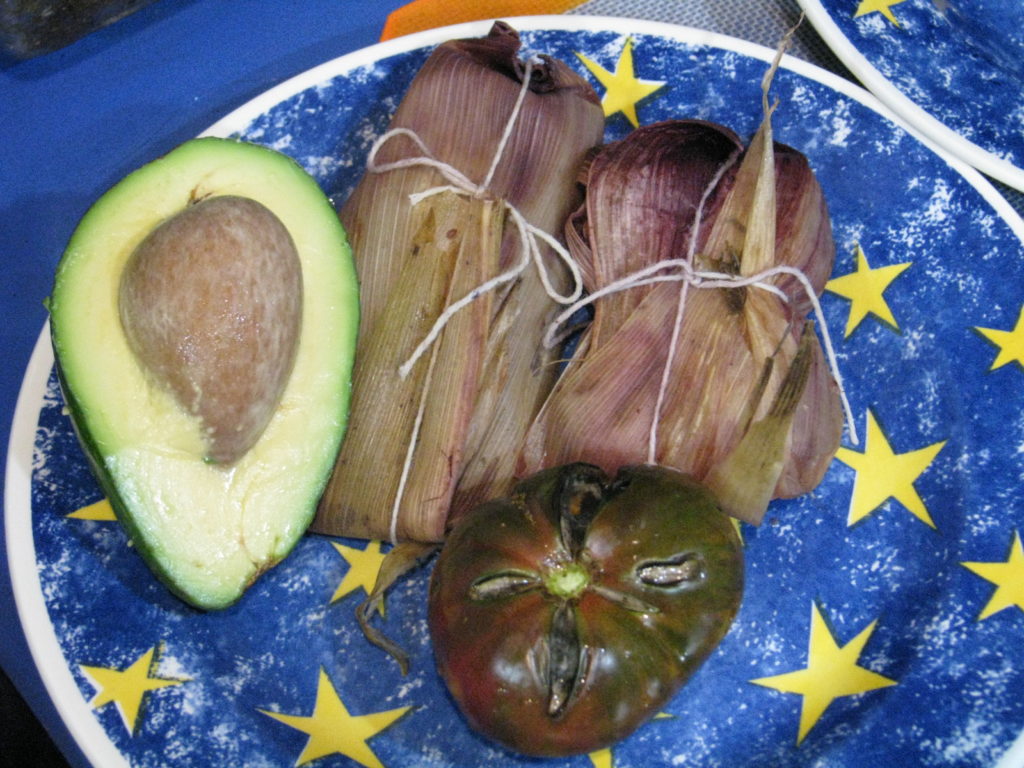

For tamales I guessed at a recipe, mixing half corn meal with half flour, a little baking powder and some vegan butter, and vegetable broth to wet. The mixture was very elastic and can certainly use work, but it was tasty and worked well to hold the filling together. The cornmeal turned a medium purple color when wet.

Soaking the husks to soften them was a treat, as their red color leached into the water making it look like wine.

For fillings I couldn’t help but go with the whole purple theme, so I steamed one of our Molokai purple sweet potatoes which are an amazing purple as well.

I also cooked up some of our frozen beet greens with onion, and used those two together with vegan cheese. A second filling was black beans mixed with cumin, oregano and our pickled carrots and jalapenos, and sweet corn with vegan cheese.

Miranda and I got such a kick out of all the colors, especially the purples. We couldn’t wait until they were steamed, which took about an hour and twenty minutes.

When the tamales were opened we were in awe. The black cornmeal had turned a very deep purple, and it was only half and half with flour! It was awesome. We enjoyed them with guacamole and, of course, our last Paul Robeson tomato because you just can’t have too many purple foods on your plate. The photo of the open tamale doesn’t do it justice.

We store the cornmeal in glass jars in the freezer. It makes excellent cornbread and cornmeal biscotti, as well as polenta and fried cornmeal mush. How fun and reassuring it is to use our own unsprayed, non-GMO cornmeal.

Coming up we’ll be planting black corn again, and a large patch of green dent as well; I want to see what pure green cornmeal looks like when cooked… maybe for Halloween dinner?

-

We Host the Smallest Bats in the United States

Our seven year-old chemical-free food forest habitat became the release site for an adorable pair. Two young rescued brothers that had been cared for by Cindy, a Project Wildlife/SD Humane Society bat team volunteer needed a safe, comfortable, food-rich home.

Our seven year-old chemical-free food forest habitat became the release site for an adorable pair. Two young rescued brothers that had been cared for by Cindy, a Project Wildlife/SD Humane Society bat team volunteer needed a safe, comfortable, food-rich home.  These two were Canyon bats, the western pipistrelle (Parastrellus hesperus) which are members of the smallest bat species in the United States. Their wingspan is at longest 8″, and their furry brown bodies are only about 6″ long.

These two were Canyon bats, the western pipistrelle (Parastrellus hesperus) which are members of the smallest bat species in the United States. Their wingspan is at longest 8″, and their furry brown bodies are only about 6″ long. These insectivores are crepuscular, meaning they feed around sunset and dawn rather than during the night. They are also not colonial bats, but are often on their own eating the mosquitoes, beetles, small moths and flies around your home. Females will usually bear twins, rare for a bat, in June, and live either by themselves or in a small maternity colony. Here in October, these two little bats were from an early summer birth and were more than ready to get out of the rescue flight cage and be off on their own.

These insectivores are crepuscular, meaning they feed around sunset and dawn rather than during the night. They are also not colonial bats, but are often on their own eating the mosquitoes, beetles, small moths and flies around your home. Females will usually bear twins, rare for a bat, in June, and live either by themselves or in a small maternity colony. Here in October, these two little bats were from an early summer birth and were more than ready to get out of the rescue flight cage and be off on their own.

They were carefully allowed to crawl up into a bat house that had been hanging empty for five years. It was facing east so as to warm in the morning, and protected from the hot afternoon sun. The inside of the bat house had rough textured wood so the very tiny little feet had texture on which to grab. We made sure than there were no containers such as buckets or nursery cans facing up; many young bats fall in and can’t get out.

It was close to our chemical-free unlined pond for easy bug access at dining times, and which has enough open space for swooping across to get a mouthful of water. They may return to the bat house, or they may fly off to find a rocky nook or tree crevice that they like better, but we sure love them being released in our garden.

In permaculture, all the animals: bats, lizards, frogs, birds etc. are vital parts of the integrated pest management system as stated by pest control st paul, and also contribute to soil fertility with their droppings, sheds, feathers, leftover meals and bodies. When you spray for insects you kill the food supply for these animals which has effects throughout the food chain. Gardens should be alive with native wild animals and insects, and not reduced to only a scavenging ground for invasive rats and domestic cats.

At dusk or early in the morning keep an eye out for bat species in your yard. They are working to keep the insect population in control.

Project Wildlife | San Diego Humane Society

San Diego County is one of the most biologically diverse areas in the United States with the greatest number of endangered species. People from all over the county bring wildlife patients to Project Wildlife for care and we are proud to be a resource that our neighbors can depend on in order to coexist peacefully with wild animals.

- Animals, Bees, Gardening adventures, Grains, Health, Heirloom Plants, Herbs, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Planting, Seeds

Growing and Eating Seeds

We eat seeds everyday. Grains, nuts, beans and, well, seeds, are all seeds. A seed is an embryonic plant covered with a seed coat. A grain is a dried fruit. In this blogpost I’m going to concentrate on true seeds.

We eat seeds everyday. Grains, nuts, beans and, well, seeds, are all seeds. A seed is an embryonic plant covered with a seed coat. A grain is a dried fruit. In this blogpost I’m going to concentrate on true seeds.Grains are usually seeds from grasses, although there are common exceptions to that rule such as the amaranth below. Seeds contain the magic that makes a plant out of a speck; a towering oak from an acorn. Seeds are highly nutritious for humans as well, but often are just used as a flavoring (think of an ‘everything’ bagel). Many have been used medically for relieving everything from eczema to mental issues. Some seeds such as grains are difficult to prepare for eating on a small scale, such as rice. Separating seeds from chaff takes a lot of steps that may not be practical for the handful of food at the end of the process. However there are many seeds that we commonly eat that are easily grown among the veggies, or even in a flower bed. Here are some that we grow at Finch Frolic Garden Permaculture:

Let’s start with one of my favorite flavors, the sesame seed.

Sesame (Sesamum indicum) seeds grow on small upright plants about 2 – 3′ high that have lovely tubular flowers.

Sesame (Sesamum indicum) seeds grow on small upright plants about 2 – 3′ high that have lovely tubular flowers.  Bees love to crawl into them. Its a pretty plant and flower, so could easily be incorporated into an ornamental area. There are both black and white sesame seed plants; the white seed is really brownish as it has a seed coat. Sesame is also called benne seed. Once harvested sesame seeds should be stored in a dark cool place or refrigerated. The seeds can be used raw, or better still lightly toasted in a dry pan before sprinkling over your food. So very yum. Tip: sesame pods become tight as they dry and then split with force, throwing the seeds away from the plant. If you want to harvest any then watch the pods as they dry on the plant and then cut and hang in a paper bag to catch the seeds as they fly, or break open with your hands.

Bees love to crawl into them. Its a pretty plant and flower, so could easily be incorporated into an ornamental area. There are both black and white sesame seed plants; the white seed is really brownish as it has a seed coat. Sesame is also called benne seed. Once harvested sesame seeds should be stored in a dark cool place or refrigerated. The seeds can be used raw, or better still lightly toasted in a dry pan before sprinkling over your food. So very yum. Tip: sesame pods become tight as they dry and then split with force, throwing the seeds away from the plant. If you want to harvest any then watch the pods as they dry on the plant and then cut and hang in a paper bag to catch the seeds as they fly, or break open with your hands.Amaranth:

Amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) is a very tasty, easily grown seed that is considered a grain. It was a major food of the Aztecs, and almost completely destroyed by the Spanish after their conquest of that civilization. Amaranth was too sneaky though and survived. It is easily digestible, high in protein and full of other nutrition. It has wild as well as ornamental varieties, but all are edible (be sure what you are eating!) Love-lies-bleeding is the dramatic name of the long red tasseled kind.

All are great for birds as well as humans.

Pigweed and lambsquarter are its weedy relatives. All of them have edible leaves, although some varieties are more tasty than others. Older leaves are better cooked. The tall varieties can grow 8′ tall or so, may need staking, and make good shade plants for others that need sun protection. When you start to see birds on the flowers then the seed should be ready. Another way to check is to gently rub the flowers between your fingers and see if seeds come off as well as the petals. If so, then over a clean, dry bucket rub the cut flowers between your fingers. Winnow the chaff away over a mesh screen or in the wind, or by gently blowing it away from the seed. Now you need to completely dry the seed in the sun, and then store in a dry, dark cool place. Use within six months for best results.

Poppy seeds:

No, not the opium kind, the lemon-poppy seed cake kind, although both are varieties of Papaver somniferum. Look for seeds for Breadseed Poppy varieties. This is another beautiful ornamental with striking seed pods that can be dried and used in flower arrangements. Poppies enjoy poor, disturbed soil. The seeds are tiny so need to be exposed to daylight to germinate. The flowers are beautiful; frail and feminine. The seed pods are rounded and have tiny holes at the top where the seeds come out of, so be careful when you are working around the drying pods or you’ll scatter seeds. Or just let some drop and they will come up next year.

No, not the opium kind, the lemon-poppy seed cake kind, although both are varieties of Papaver somniferum. Look for seeds for Breadseed Poppy varieties. This is another beautiful ornamental with striking seed pods that can be dried and used in flower arrangements. Poppies enjoy poor, disturbed soil. The seeds are tiny so need to be exposed to daylight to germinate. The flowers are beautiful; frail and feminine. The seed pods are rounded and have tiny holes at the top where the seeds come out of, so be careful when you are working around the drying pods or you’ll scatter seeds. Or just let some drop and they will come up next year.

Allow the pods to dry on the stem and then carefully cut. Shake the seeds out into a jar and store in a cool, dark place. Use raw or lightly toasted. Be sure not to eat them before taking a drug test, or you’ll test positive.

Allow the pods to dry on the stem and then carefully cut. Shake the seeds out into a jar and store in a cool, dark place. Use raw or lightly toasted. Be sure not to eat them before taking a drug test, or you’ll test positive.Basil seeds:

Basil seeds aren’t well known for their culinary use in the US, but they are nutritious and useful. The seeds of the sweet basil plant (Ocimum basilicum) not Holy Basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum), when soaked make the water gelatinous, as chia seeds do, so are used to thicken drinks and foods. You don’t have to soak basil seeds to use them though. The flowers are delightfully edible as well. Use them for additional flavor and nutrition by tossing them raw into salads, salad dressing, breads, or just about anything. Letting some of the basil plant go to seed (while pinching other stems to keep it leafing) will attract small native pollinators to your garden. When the flowers dry, the seeds are ready to be shaken off into a clean, dry bucket or bag.

Basil seeds aren’t well known for their culinary use in the US, but they are nutritious and useful. The seeds of the sweet basil plant (Ocimum basilicum) not Holy Basil (Ocimum tenuiflorum), when soaked make the water gelatinous, as chia seeds do, so are used to thicken drinks and foods. You don’t have to soak basil seeds to use them though. The flowers are delightfully edible as well. Use them for additional flavor and nutrition by tossing them raw into salads, salad dressing, breads, or just about anything. Letting some of the basil plant go to seed (while pinching other stems to keep it leafing) will attract small native pollinators to your garden. When the flowers dry, the seeds are ready to be shaken off into a clean, dry bucket or bag. Coriander:

You probably know cilantro or Chinese parsley as the love-it-or-hate-it herb found in salsas and many Mexican or East Indian dishes. Cilantro (Coriandrum sativum) seed is called coriander. Coriander seed is usually used ground and used in curry mixtures, soups and meat dishes. It is an historical herb, being used in ancient India, China and Egypt. It has a kind of lemony taste that is unique.

Celery seeds:

Celery (Apium graveolens) seeds are marvelous savory additions to soups, particulary tomato. I grind it up in a mortar and throw it in soups and stews to round out the flavor. We grew celery one year -although I have no photos of it – and because of the warm weather the celery stalk flavor was quite strong. However the seeds were delightful. Celery is a cool-season plant and the stalks should be covered to keep pale green and mild flavored. Or just let them grow for the seed. There is a wild variety that grows in marshlands, but please be very careful if you harvest from it because it looks similar to the very poisonous water hemlock (Cicuta).

Fennel:

If you’ve sipped ouzo, aguardiente or anisette, you’ve tasted the seeds of the fennel plant. Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) is the brother of anise, and both have escaped gardens to be a troublesome weed. Fennel bulbs are absolutely amazing lightly steamed, and then baked in vegan butter and topped with vegan Parmesan. The leaves are fantastic stirred into eggs or salads, and the seeds are incredible flavorings for baked goods, candies and obviously alcohols. Miranda candied fennel seeds for me. They have been used to try and mask cigarette or alcohol breath, but really… who is kidding who? They do make a great breath freshener chewed. The plants are frondy, tall and have pretty umbels of flowers that native insects love.

Grow some for the bulbs (protect them from gophers!) and let others go to seed. Cut and hang upside down to collect the seed in a bag or else you’ll have fennel everywhere. And that may not be a bad thing.

Grow some for the bulbs (protect them from gophers!) and let others go to seed. Cut and hang upside down to collect the seed in a bag or else you’ll have fennel everywhere. And that may not be a bad thing.Sunflower

I don’t know anyone who isn’t familiar with sunflower seeds; certainly the shells were routinely spit out all over campus as a cool snack when I was in college and probably still are. At least they are biodegradable. Sunflowers (Helianthus annuus) are one of the few edible seeds native to North America, and they are protected in an attractive hull. Some varieties are small, multi stemmed and ornamental, and others are grown for their fabulously large seed heads. Birds love eating the green leaves as part of their healthy diet, so grow extra. The seed heads should be left to dry on the stalk, and then cut and shaken to de-seed. Good pollination is important to produce seeds with good ‘meat’ inside.

Eat them raw or toasted; they are full of good things for your body. (Miranda is 5’1″ in the photo, not tiny. I like that one of the heads seems to be checking her out.)

Dill

Dill (Anethum graveolens) is another double happiness plant. The leaves are tremendous used fresh or dried, and the seeds are fantastic as well. We use the whole seed heads in our dill pickle recipe. It goes well with fish, or in our case vegan fish. Grind them or use them whole, but definitely stir them into sauces, soups, dressings, dips, etc. Dill, like fennel, will reseed, but that isn’t a bad thing. They look pretty much like the fennel plant above.

Caraway:

We’ve grown caraway (Carum carvi) in the past, but I have no picture for you. Just refer to the photo above of the fennel and it will be close, as they are in the carrot family. You’ll find caraway in rye breads, liquors and cheeses, and in some areas the young leaves and roots are also eaten. They are dried and harvested just like the fennel and dill.

There are other seeds that we haven’t grown. We’ve tried to grow cumin and annatto seeds, but have failed to make them germinate; there is always next year. Some seeds are so small, such as chia, that you’d have to grow a lot of plants to harvest just a little seed. Seeds are such a vital nutritional and flavorful part of our diets, and so fun to grow that everyone should sprinkle edible seed-bearing plant seeds throughout their garden. As seeds dry and keep fresher longer than dried leaves (such as basil or dill), that fresh taste of the garden can last through until next year’s harvest time again.

- Gardening adventures, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Recipes, Seeds, Vegan, Vegetables, Vegetarian

Glorious Beet Greens

Did you know that beet greens are gloriously edible? That they are tender, not bitter, mild, easily cooked and full of nutrition? As I was never a beet lover, I didn’t know that either. I’ve loved Swiss chard with its slight bitterness, intense flavor,

Did you know that beet greens are gloriously edible? That they are tender, not bitter, mild, easily cooked and full of nutrition? As I was never a beet lover, I didn’t know that either. I’ve loved Swiss chard with its slight bitterness, intense flavor,  and huge leaves

and huge leaves  but I wouldn’t go near a beet until a few years ago. I would make vegetarian borscht (Russian beet soup) for my father but never taste it and hope that it came out well. Then I was gifted with a jar of pickled beets and I had to try them to not insult the giver… and I liked them. Strangely, pickled beets go really well with curry. So Miranda and I grew beets, and let some go to seed.

but I wouldn’t go near a beet until a few years ago. I would make vegetarian borscht (Russian beet soup) for my father but never taste it and hope that it came out well. Then I was gifted with a jar of pickled beets and I had to try them to not insult the giver… and I liked them. Strangely, pickled beets go really well with curry. So Miranda and I grew beets, and let some go to seed. This year we had hundreds coming up in the garden.

This year we had hundreds coming up in the garden. Good thing that we found out about the greens. Now I’d grow beets just for their greens and pull some early for the root. Just keep cutting the greens and the beet root will continue to produce leaves, although the root will grow large and too tough to eat. Then allow it to go to seed.

Good thing that we found out about the greens. Now I’d grow beets just for their greens and pull some early for the root. Just keep cutting the greens and the beet root will continue to produce leaves, although the root will grow large and too tough to eat. Then allow it to go to seed. We planted many different kinds of beets, and although the roots tasted a little different the tops all tasted just as good. We also planted sugar beets, and they were so very sweet and yet earthy that I really didn’t care for them as a vegetable. My favorite beet root is chioggia which as lovely red circles when sliced. We purchased all of our beet seeds from Baker Creek Organics.

Beets have deep tap roots, therefore they are excellent ‘mining’ plants in a plant guild. They bring nutrients up from deep in the soil, and what leaves you don’t eat can be put back on or in the ground to create topsoil.

Beet greens can be torn up and put into a salad raw or used in place of lettuce on a sandwich. To cook beet greens, wash and tap off excess water, tear up and put into a medium hot pan that has a little olive oil coating the bottom. Stir until wilted. You can eat them from this point as they are not stringy. If the leaves are older I’ll put a little more water in if needed, turn down the heat, cover the pan and let the leaves steam for a few minutes. You don’t need salt or salty broth as the leaves have a strong enough taste. Eat them with vegan butter as a side dish, stir them into omelettes or frittatas, or use them any way you would spinach.

Freezing beet greens is easy. Wash them, shake off excess water, and put into freezer bags. They aren’t mushy black when thawed and cooked.

Grow your extra organic beets and leave some of them just for harvesting greens. You’ll want to fill your yard and your plate with them!

- Animals, Bees, Birding, Gardening adventures, Natives, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Predators, Reptiles and Amphibians, Varmints

Insects: Pest or Partner?

Ladybug on ragweed, chowing down on the aphids. Finch Frolic Garden has been insecticide-free since it was first planted. It is a wildlife habitat as well as a food forest, and there are no chemicals at all used. Instead we rely on that habitat to create an integrated pest management system you can click to see how it works.

Western fence lizards are in and out of all of our veggie beds. We use no fertilizers other than compost, so they are safe. The abundant frogs and lizards balance out most of the insect populations, and the birds, particularly bush tits and the other smaller gleaners, do their share.

A surprise visit from a skink! Welcome, little bug eater! It may seem counter-intuitive to invite in and create habitat for insects when insects do the most damage.

A Baja California Treefrog, a.k.a. Pacific Chorus Frog (Pseudacris hypochondriaca hypochondriaca), clinging to the PVC pipe in the beet bed. He’s keeping the bugs in check while being cute. But like humans, bugs are bug’s own worst enemy. Bring in the native insects!

Observation plays an enormous role in successful pest management says this Bed Bug Specialist Los Angeles California; what better excuse for sitting in your garden looking at flowers?

Mexican Bush Katydid (Scudderia mexicana) on fennel. For that is where you’ll see most of the beneficials.

A tiny jumping spider (family Salticidae) on yarrow. Spiders eat a lot of insects. The nectar draws in the bugs, and the spider waits. In dryland areas everything is smaller: smaller tree canopies, smaller predators, smaller prey, and smaller insects. There are over 300 species of bee native to San Diego alone. None of them produce honey -there are no native honeybees to North America – but they are very important and very overlooked pollinators. Planting native plants, which have adapted over time to provide the best possible food sources in the most attractive packages, will be optimal for a native garden. Allowing non-natives that are also attractive to good bugs go to flower, along with the natives, is good too. For instance, dill, mint, basil, fennel and carrot all produce clusters of tiny flowers.

Blooming cilantro next to peas: both are good non-native small insect food sources. Take a good squint at them and you’ll see very tiny creatures dining out on the pollen and nectar, and possibly each other.

This scary-looking character (Chrysoperla rufilabris) is a wonderful friend, voraciously hunting many kinds of insects in adult, larval and eggs forms.

Lacewing larva are ugly ducklings that grow into lovely — and equally predatory — fairy-like adults. Keeping a food supply for predatory insects is important to keep them in your garden. People buy ladybugs — most of which are non-native — and release them into a garden hoping they’ll linger and take care of any insect problem that might come up. Well, those poor bugs who survive packaging are hungry and thirsty. If there aren’t drops of water to sip on or aphids to munch right away, they have to go looking for them to survive. So leaving patches of plants with small infestations of aphids or other insects is important, as hard as that may be to do.

Recently while installing more raised pallet beds in the vegetable garden I was about to pull out a batch of ragweed.

Ragweed covered in aphids. Its a native here, but an invasive one as it travels via underground runners and by seed. This batch was covered in aphids. Miranda, with her good eyesight, luckily stopped me. She saw dozens of ladybug larvae happily munching on all of those aphids.

Ragweed chock full of hungry ladybug larvae and hatched adults. They cleaned the plant of aphids and went to work on the rest of the garden. There were adult ladybird beetles as well, but the number of larvae was incredible.

Nom! The ragweed stayed. Eventually it was sprinkled with white aphid carcasses sucked dry by ladybug larvae. In a couple of weeks, the aphids were gone, the plant looked absolutely clean, and the ladybugs had had successful reproduction and had flown off to work in other areas of the garden and possibly in my neighbor’s yard. You are welcome. Then I pulled out the ragweed. We have plenty of it elsewhere for future ladybug mating sites.

Inspection of native plants at a friend’s house which were besieged by scale and aphids showed two things: one, that Argentine ants were farming insect on the leaves of the plant, and needed to be controlled, and that these plants also had the local rescue squad on hand. Thanks to Miranda again, she saw many types of native predatory insects feeding on the invaders.

Hoverflies or flower flies like this Four-spotted Aphid Fly (Pseudodoros clavatus) are not only our most common generalist pollinator, but also an important predator of plant-sucking insects such as aphids and thrips.

Larvae of Pseudodoros clavatus feasting on Oleander Aphids (Aphis nerii). Oleander Aphids are commonly found on milkweed. We didn’t want to sprinkle food grade diatomaceous earth on the leaves or do anything to kill off the good guys, so we put borax ant bait in protected containers around the base of the plants and left them alone. The ants would die off and stop farming the bad guys, and the good guys would have great meals and be healthy and hardy enough to reproduce on site. The plants would recover and the natives would win.

The worst gardening policy is the ‘squish first and ask questions later’ one. Although this long-haired cutie might look like the dastardly mealybug, it’s actually the larvae of the Mealybug Destroyer beetle (Cryptolaemus montrouzieri), a naturalized predator species that saved the California citrus industry once upon a time and which continues to covertly lend a hand in orchards and gardens every day. Plants communicate in many different ways, and one of the ways is through scents that we cannot detect. These volatile organic compounds (VOCs) are released for various reasons and detected by surrounding plants. Native plants will release an alarm VOC when being attacked by insects that other natives pick up on, and they in turn release VOCs that attract the native predatory insects that will eat the pest. You can get more info on how to deal with pests. Having lots of native plants integrated in your landscape benefits your non-natives by calling in the rescue squad when the bad guys show up. Non-native plants, of course, release VOCs as well, but they are speaking a different language; their chemicals may not be recognized by the other plants, or they are signalling for beneficial insects that don’t live in the area. By providing good habitat – bird boxes, sources of water for birds, lizards, frogs, toads and insects, having mulches and native bee nesting boxes around the property, allowing some plants to flower, and of course, not using insecticide, you’ll have a balanced ecosystem full of wildlife in no time.

Industrious Orange-crowned Warblers (Oreothlypis celata) can be seen poking through bushes, trees and even tall lush grass prowling for small insect prey. Remember that even if a product is from plant sources – such as neem oil or pyrethrum, doesn’t mean that it isn’t powerful. No insecticide will kill the target species and leave all the good guys alone. Scorched earth policy is never the best way to go in nature. Sprinkling food grade diatomaceous earth just where the bad bugs are and not liberally spreading it around, or using a soap and water spray on infested leaves, can help. Just look first and see if there are signs of beneficials already there working for you.

This female braconiid wasp’s tail-like long, thin ovipositor is a weapon of population regulation. She uses it to inject her eggs into the bodies of her prey — fruit flies in this species — and her maggots eat their hosts from the inside. Remember too that if you purchase plants that have been treated with insecticide, particularly those with systemic insecticides (which means they work internally throughout the plant), they will kill anything that takes a bit out of them. The poison goes through the pollen and nectar as well. So birds nibbling the leaves, pollinators and beneficial predatory insects having a meal, butterfly caterpillars, and the insects that eat all of the above, will all be poisoned. If that milkweed you bought to feed the Monarchs don’t have aphids on them, be suspicious. Those tags at the big box stores that say the plants have been treated with insecticide – neonicotinoids – that are safe, are excluding facts about what else they effect. Systemics stay in the plant, possibly for the life of the plant. They don’t go away. GMO seeds have had their DNA modified to accept the use of chemicals, both herbicides and insecticides. Glysophate, a derivative of Agent Orange, is now found in mother’s milk, in human and animal tissue, and in most soil. We have to stop using chemicals for the health of ourselves and our ecosystem. So buy plants and seeds from sources you can trust. Just because the big box stores offer a good return policy doesn’t validate their products. You are buying inferior plants that are toxic to beneficial insects. That bug-free milkweed plant will kill the Monarch caterpillars feeding on it. The more you demand and support chemical-free plants, the more suppliers there will be. On my Resources page under Shopping I have listed many wonderful sources for plants and seeds online, but look locally first.

A minute pirate bug (Orius tristicolor) scans the deck of this native Dove Weed (Croton setigerus) leaf for any of the mites, thrips, aphids and caterpillars it makes its vittles from. No prey, no pay, and dead bugs tell no tales about this tiny but deadly predator! Get to know your native insects. Have a seat by the flowers and take a good look – with a magnifying glass if necessary – and be amazed at the hundreds of little workers you didn’t even know that you had.

- Compost, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Microbes and Fungi, Other Insects, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Planting, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water Saving, Worms

Building and Filling Free Raised Beds

I grew vegetables in raised beds made of old bookshelf wood for many years. Then several years ago we buried that wood along with other biodegradable material in the vegetable garden and grew in the earth This is the best method of growing vegetables. However, the ongoing drought caused plant scarcity and otherwise manageable wildlife then foraged in desperation. Gophers began an onslaught of our vegetables and being a no-kill garden (except for Argentine ants) we tried many kind methods of discouraging them. Finally this year after a dry warm winter, anticipating more animal depredation, I took a friend up on their offer of free used pallets.

I grew vegetables in raised beds made of old bookshelf wood for many years. Then several years ago we buried that wood along with other biodegradable material in the vegetable garden and grew in the earth This is the best method of growing vegetables. However, the ongoing drought caused plant scarcity and otherwise manageable wildlife then foraged in desperation. Gophers began an onslaught of our vegetables and being a no-kill garden (except for Argentine ants) we tried many kind methods of discouraging them. Finally this year after a dry warm winter, anticipating more animal depredation, I took a friend up on their offer of free used pallets.  We sorted through stacks of pallets and found those stamped with the same name. These pallets are untreated raw pine and of a manageable and portable size. I cut each pallet in half and then nailed and screwed them together. One raised bed needed three pallets. We then covered the bottom with hardware cloth. The areas where the raised beds were to go were leveled and in several cases, de-Bermuda grassed.

We sorted through stacks of pallets and found those stamped with the same name. These pallets are untreated raw pine and of a manageable and portable size. I cut each pallet in half and then nailed and screwed them together. One raised bed needed three pallets. We then covered the bottom with hardware cloth. The areas where the raised beds were to go were leveled and in several cases, de-Bermuda grassed. The pernicious weed had infiltrated our good soil and so shovelful by shovelful we turned and picked. The stolens were unceremoniously tossed into a trashcan which will solarize in the burning hot summer to come, and will then be used in compost.

The pernicious weed had infiltrated our good soil and so shovelful by shovelful we turned and picked. The stolens were unceremoniously tossed into a trashcan which will solarize in the burning hot summer to come, and will then be used in compost. On top of the leveled ground we placed cardboard. This provided a grass and gopher barrier to the bottom of the bed. Although the cardboard will break down over time, it will in the short run discourage gopher tunneling and weeds. The new pallet bed was placed on top of the cardboard.

Here is one of the tricks of having a raised bed in a hot climate: insulate it! Anything raised above soil level in hot climates are quickly heated and dried out. Raised beds notoriously have dead zones around the edges where the heat cooks the soil, killing microbes and sucking water out of the bed. Lining the inside of the bed with thick cardboard is one way to help insulate the bed, as well as planting cascading plants on the southwest side, or bushy herbs in the ground outside of the bed, or even fastening flakes of straw around the outside. With the pallets we had room to not only line the inside of the bed, but stuff cardboard down into the gaps all around the bed. We repurposed a lot of cardboard.

Here is one of the tricks of having a raised bed in a hot climate: insulate it! Anything raised above soil level in hot climates are quickly heated and dried out. Raised beds notoriously have dead zones around the edges where the heat cooks the soil, killing microbes and sucking water out of the bed. Lining the inside of the bed with thick cardboard is one way to help insulate the bed, as well as planting cascading plants on the southwest side, or bushy herbs in the ground outside of the bed, or even fastening flakes of straw around the outside. With the pallets we had room to not only line the inside of the bed, but stuff cardboard down into the gaps all around the bed. We repurposed a lot of cardboard. To fill the bed, we began with old sticks, limbs and logs as we had them. We layered these items as they were available, making sure that earth was touching each layer, and balancing green plant material with the brown as you would in a compost situation: dried tomato vines, fresh passionvine prunings,

To fill the bed, we began with old sticks, limbs and logs as we had them. We layered these items as they were available, making sure that earth was touching each layer, and balancing green plant material with the brown as you would in a compost situation: dried tomato vines, fresh passionvine prunings,  cut back rose canes, sycamore leaves, heavy clay taken from a new asparagus bed, silt from the rain catchment basins,

cut back rose canes, sycamore leaves, heavy clay taken from a new asparagus bed, silt from the rain catchment basins, kitchen scraps including bags of orange rinds after juicing, poopy chicken dirt from inside the hen house,

kitchen scraps including bags of orange rinds after juicing, poopy chicken dirt from inside the hen house,  poopy newspapers from the cages in which we kept sick hens indoors (crop binding), decomposable trash such as used tissues, paper towels, cotton ear swabs, junk mail (not glossy or plastic),

poopy newspapers from the cages in which we kept sick hens indoors (crop binding), decomposable trash such as used tissues, paper towels, cotton ear swabs, junk mail (not glossy or plastic),  hair, cotton balls, old cotton T-shirts, and corn husks which many people don’t know are used for compost purposes (visit https://homewarranty.firstam.com/blog/corn-husks-not-just-tamales to get all the details). As we built the beds, we’d take our time filling them as we produced ‘waste’ materials, and threw them in.

hair, cotton balls, old cotton T-shirts, and corn husks which many people don’t know are used for compost purposes (visit https://homewarranty.firstam.com/blog/corn-husks-not-just-tamales to get all the details). As we built the beds, we’d take our time filling them as we produced ‘waste’ materials, and threw them in.

When the bed was filled (and understanding that the contents would settle) and watered in with rainwater from our 700 gallon tank, we topped it with microbially rich soil from the garden beds (making sure there weren’t any grass bits hiding in it).

When the bed was filled (and understanding that the contents would settle) and watered in with rainwater from our 700 gallon tank, we topped it with microbially rich soil from the garden beds (making sure there weren’t any grass bits hiding in it). I stuck pieces of old 1′ PVC pipe evenly along the sides of the pallets prior to stuffing with cardboard, so that if needed I could insert wood or bamboo pieces and either build an upright sturdy trellis for climbers, or even make arches from bed to bed on which I can grow vines.

For irrigation, I connected each bed to its own set of overhead sprinklers. Each bed has its own shut off.

For irrigation, I connected each bed to its own set of overhead sprinklers. Each bed has its own shut off. The pipe is resting on the opposite pallet as support, and the joint where it els across the bed are threaded pieces, so the entire length can be raised and pulled out of the way so working in the bed can be easy.

The pipe is resting on the opposite pallet as support, and the joint where it els across the bed are threaded pieces, so the entire length can be raised and pulled out of the way so working in the bed can be easy. The irrigation is hooked up to our well water and is on the irrigation timer for a brief shower every other day. With a lasagna garden, once saturated water will be held in the organic materials that make it up, so after initial regular watering for seed sprouting or hardening off transplants you won’t need to water as much. Roots will grow very deeply.

The irrigation is hooked up to our well water and is on the irrigation timer for a brief shower every other day. With a lasagna garden, once saturated water will be held in the organic materials that make it up, so after initial regular watering for seed sprouting or hardening off transplants you won’t need to water as much. Roots will grow very deeply.Because we allow some vegetables to go to seed, we had to transplant vegetables from the ground where the raised beds were placed, into the raised beds.

We have a forest of beets, fennel, perpetual spinach, onions, peas, arugula and lettuce in what is still in the ground, and have transplanted selections from these into the beds along with planting seeds. Fortunately we love beet greens, which don’t taste like beets and are more mild than Swiss chard.

We have a forest of beets, fennel, perpetual spinach, onions, peas, arugula and lettuce in what is still in the ground, and have transplanted selections from these into the beds along with planting seeds. Fortunately we love beet greens, which don’t taste like beets and are more mild than Swiss chard.

Into one bed we’ve planted potatoes in good soil at the bottom, and are gradually filling in with straw as the plants grow. We used leaves in the soil mix, but no woody bits or other lasagna garden materials because we didn’t want to dig potatoes out of piles of old wood, nor burn the potatoes with composting materials in the shallow soil layer.

I am not a good carpenter. I however am great at figuring out what should have been done after I’ve done something. Here are some tips on building pallet beds:

I had thought about placing them on top of flat pallets to be raised off of the ground, so even less susceptible to gophers and grass, but I fortunately nixed that idea before it was enacted. The reason is that that space would be a wonderful habitat for mice or rats, or even snakes. Much as we welcome non-venomous snakes into our garden I really don’t want to startle one with my feet as I’m leaning over a bed. Of course, they would take care of the mouse and rat problem, so maybe it would be a good thing.

I had several bags of 16p galvanized nails given to me years ago, a rescue from a construction dumpster. I mean, kitchen trash-sized bags. I can’t move them, and they sit in my large shed. I opted to use some of them for this project. It was difficult hammering them into the knotty wood of the pallets, and often the holes had to be pre-drilled. Nailed wood also can pull apart, so braces across the width of the pallet to prevent bulging would have been a fantastic idea. For the last two I resorted to screws, which are far easier to both install and remove. Perhaps the nails will have to go to Temecula Recycling. If I can lift them.

We needed to build the beds quickly, as planting season bore down on us here in San Diego even earlier than usual. Here at the beginning of April we are far behind because we haven’t planted out tomato, squash, melon or cucumber seeds yet. Whew! So the beds are not beautiful, but they are functional. You can pretty up pallet beds by attaching wood around the outside, or straw flakes, or other material, and by putting wood around the top. Especially if it is repurposed wood. If you have mouse problems, then try attaching chimney flashing or other wide strips of metal around the base of the bed so that they cannot climb up the sides.

My entire vegetable patch is surrounded by a chicken wire fence, so bunnies can look but they cannot touch. We don’t have squirrels anymore in the garden because California ground squirrels like to see all around them, and our dense food forest is much too scary for them to be comfortable. Using a mild shock wire around the beds or garden fence, using metal flashing to prevent climbing, or enclosing a small garden with wire would all be ways to prevent squirrels and rats from feasting.

We covered the surrounding ground with cardboard and topped with free wood chips, for sheet mulching.

This cools the soil, prevents weeds from emerging, helps choke out the Bermuda grass, and also keeps the gopher at bay. He or she must push droppings out of the hole, and if they hit cardboard, or have a shower of bark come down on them, they will go elsewhere.

This cools the soil, prevents weeds from emerging, helps choke out the Bermuda grass, and also keeps the gopher at bay. He or she must push droppings out of the hole, and if they hit cardboard, or have a shower of bark come down on them, they will go elsewhere.Because we used non-sterile garden soil as a topper, we’ve had some weed seeds germinate but also some pleasant surprises. We planned on planting dill but found it popping up in our polyculture planting. We had several potato bits sprout, so they needed to be moved into the potato bed. Purslane, which is a weed but also one of the most nutritious greens you can eat, loves the beds so we are harvesting it regularly for chicken feed, personal use and also for making green smoothies as liquid compost for our citrus trees. Because we don’t use chemicals of any sort in the beds, there are a number of native western fence lizards loving the heck out of the beds and helping with our integrated pest management.

Some crops such as corn and tomatoes will need to go into the soil; so far gophers haven’t eaten corn, and the tomatoes can go into gopher cages up against fences or around the property on trellises or trees. The strawberries, Jerusalem artichokes and horseradish seem safe in the ground as well.

Our raised beds are working beautifully already, and the dirt and organics inside of them will be building good soil month after month until it is gorgeous compost. Except for labor, wire and a few PVC parts, they were free to build and free to fill. They can be topped off with good compost after a season, or even given another layer of old tomato vines and dried plant scraps topped with compost for the next planting season if needed. But it shouldn’t unless the height of the soil needs building, because the soil inside the bed is improving all the time.

Give it a try, and make it more attractive, and you’ll have wonderful, safe vegetables and no green waste at all.

- Bees, Birding, Compost, Frost and Heat, Fungus and Mushrooms, Gardening adventures, Hugelkultur, Irrigation and Watering, Microbes and Fungi, Natives, Other Insects, Perennial vegetables, Permaculture and Edible Forest Gardening Adventures, Planting, Predators, Quail, Rain Catching, Recycling and Repurposing, Reptiles and Amphibians, Seeds, Soil, Water, Water Saving, Worms

What a Difference Mulch Makes

Two years ago friend sheet-mulched her very hard, dry dirt yard using cardboard and newspaper topped with very large chunk free wood chips. Last year into this were planted a scattering of California native plants. Most of them have thrived, even surviving a frost and many 100F + days. These have been minimally watered. This week in March, after very low seasonal rainfall, we set off to plant more natives. What we found under the mulch was amazing. That light brown dirt was now moist, worm-filled soil. Under what was left of the cardboard were beautiful fungal hyphae breaking down the under layer of bark chunks into a fine surface compost. The shovel slide through the newspaper and into the ground making for very easy digging.

Two years ago friend sheet-mulched her very hard, dry dirt yard using cardboard and newspaper topped with very large chunk free wood chips. Last year into this were planted a scattering of California native plants. Most of them have thrived, even surviving a frost and many 100F + days. These have been minimally watered. This week in March, after very low seasonal rainfall, we set off to plant more natives. What we found under the mulch was amazing. That light brown dirt was now moist, worm-filled soil. Under what was left of the cardboard were beautiful fungal hyphae breaking down the under layer of bark chunks into a fine surface compost. The shovel slide through the newspaper and into the ground making for very easy digging.  The soil smelled good and felt alive.

The soil smelled good and felt alive.Then we wanted to enlarge the planting area past the mulched area, and it was as if we were digging on another property. The shovel barely entered the dirt, and then hit hardpan within an inch of the surface. We had to chop and scrape holes to plant in. Once we did, we heavily sheet mulched around the plants.

Both of these areas, separated by a foot, have had the same rainfall and temperatures, but the mere existence of a thick layer of sheet mulch caused moisture and coolness to be retained, caused protection from hard rain, frost, high heat and dryness, compaction and wind. Just this easy combination of waste materials – wood chips and cardboard – made an incredible change in the soil structure and water retention.

Both of these areas, separated by a foot, have had the same rainfall and temperatures, but the mere existence of a thick layer of sheet mulch caused moisture and coolness to be retained, caused protection from hard rain, frost, high heat and dryness, compaction and wind. Just this easy combination of waste materials – wood chips and cardboard – made an incredible change in the soil structure and water retention.Last summer when the outside temperature was in the 90’s we dug into a pile of bark chips. On the top the wood was almost hot. Three inches down, it was cool and moist even though it hadn’t rained for months. A difference of night and day. This summer I’ll obtain a compost thermometer and take readings.

Leaving the soil bare is like going out in all weather unclothed. Your skin will burn and you’ll become dehydrated in summer; you’ll freeze and also become dehydrated in the cold. In heavy rain and hail you will try to protect yourself by becoming as small a target as possible. Although the soil isn’t cowering, it is being pounded down and de-oxygenated under the onslaught of weather. With no air in the topsoil water runs off rather than sinks in. Soil bakes and there is no microbial life in the desert of the uncovered topsoil. The soil freezes and frosts, and microbes are killed; the moisture in the soil evaporating with the coming of spring. All of this damage is preventable by the application of several layers of mulch, or sheet mulch. You wouldn’t think of being outside for a long time in harsh weather without clothing, so protect your soil the way nature intends, with a carpet of organic matter.

The cardboard had gone on top of weeds. No additives were used in planting, such as gypsum, fertilizer or compost. Watering is done on an as-needed basis with a hose. I am always thrilled and awe-struck when, over and over again, I see proof of what simple soil conservation efforts have on soil building.

California poppies seeds had been planted in the planting holes the year before, and their seeds have rooted in the bark mulch. Their roots will hold the mulch together and also help change it into soil, as poppies are colonizers helping repair disturbed soil. For the price of a packet of seeds, our friend now has the beginnings of a wildflower meadow filling out the spaces between native flowering plants.

Good soil begins the food chain, beginning from what science can so far tell from microscopic mycrobes and ending in this property at least perhaps at the nesting red tailed hawk in the nearest tree, or perhaps the largest local predator, the coyote. Meanwhile the butterflies and other native insects, and all the song birds, will be on display for our friend’s enjoyment.

The sheet mulching will continue on over the slope, and as we plant we mix in pieces of old wood, we plant in shallow depressions in the ground to capture moisture and coolness, we dig a small fishscale swale above the plant to capture flowing water, and we sheet mulch heavily. It will be fascinating to keep checking that poor dirt as it regains microbial and fungal life simply through the protection of sheet mulch.